I reverse-engineered Kindle to build AI audiobooks

The absurd lengths I went to for 8-minute audiobook snippets

Imagine this:

You usually read on a Kindle Paperwhite, but on the way to dinner you only have your phone with you, so you use the Kindle app on your phone while on the subway. You get off the subway and have an 8 minute walk to the restaurant, during which you can no longer read.

Wouldn’t it be nice to listen to an audiobook on that walk? But you don’t usually listen to audiobooks, and you only really need it for a few minutes, so you don’t want to buy the whole audiobook. Plus, your book isn’t Whispersync-for-Voice enabled, so even if you had the audiobook and listened, your progress wouldn’t sync—you’d have to manually find the right spot in the book.

This very relatable scenario is just my life, so I built an app to generate audiobook snippets on-demand with AI—and they always sync.

1.0 Decoding Kindle

My original idea was to have an app that would automatically swipe/screenshot the Kindle app and use OCR to extract text, but Apple doesn’t allow that level of device control (for good reason). So I had to find a way to programmatically get the content of the book and sync reading progress.

1.1 Content Deobfuscation

After a bit of searching, I discovered that Kindle ebook files download as .tar and have to be deobfuscated—the actual page images are embedded as a series of XOR’d glyphs rather than plain text. I got lucky on timing; PixelMelt had just posted an article on how to reverse engineer the obfuscation.

I did this project in November and had been hearing good things about Codex so thought this would be a nice opportunity to give it a try; PixelMelt didn’t publicly share the code so I’d have to recreate it. I gave both Codex and Claude Code the article content and let them run with it. Both failed pretty miserably1, but Codex failed less miserably, so I decided to switch over for the rest of the project.

Amidst its failure Claude did uncover a more recent article with improvements to the original deobfuscation methodology—render all the glyphs, stitch them together into their page structure, screenshot the page, OCR the screenshot. Armed with this new approach + some more intentional instructing, Codex got the job done pretty quickly.

1.2 Kindle Access

That solved extracting text once I had the .tar file, but I still needed to be able to programmatically download the file and update reading position in the book. I pretty quickly found the kindle-api library for access to the Kindle Web API, but there were two problems:

Only books you buy on the Kindle store show up in the web reader, but I purchase most of my books elsewhere

The library only supported retrieving high-level book info

I spent ~45 minutes with mitmproxy to try to reverse engineer the Kindle Mac reader’s API, but it was a lot harder to figure out than the web API and I didn’t want to spend the whole project just reverse engineering, so I decided that being limited to books bought on the Kindle store was fine.

The original repo has you log into the web reader, inspect element, and manually copy cookies (valid for a year) from the network requests. The endpoints I needed had additional shorter-lived tokens, though, so I needed a better way to collect the info.

Rather than trying to automate with puppeteer/playwright and beat Amazon’s captcha, I just put an embedded browser in the iOS app—the user logs in manually, and the app grabs the required cookies from the network requests.

2.0 Building the App

Now that I had all the pieces, time to put it together!

2.1 Architecture

I used Fastify for the server and SwiftUI for the iOS app, with WKWebView + injected JavaScript to capture Amazon credentials from network requests. The server calls my Python deobfuscation code as a subprocess and relies on my fork of kindle-api for Kindle access.

The initial version was minimal: download the book content, convert it to text, and serve text chunks to the app. Before integrating text-to-speech and reading progress, I had to make a decision about data storage.

There are a lot of artifacts to manage—raw .tar files, extracted JSONs, page images, OCR text, audio files. I could have set up S3 or a database, but that felt like overkill for a self-hosted single-user app. Instead, I went with an the simplest option: store everything in a local data folder within the server. If the server dies, so does my data, but for relatively ephemeral audiobook snippets that’s probably fine.

2.2 Audio & Position Sync

I used ElevenLabs for text to speech; they have a with-timestamps endpoint that provides the necessary character-level timing information to be able to sync reading progress with position. I stored mapping of audio timestamps to Kindle position IDs at 5-second intervals, so the app knows where to update progress as playback advances.

I then added a frame-synced listener to the audio playback that checks every frame if the current time has crossed a benchmark checkpoint. When it does, it hits the /books/:asin/progress endpoint with the corresponding Kindle position ID, syncing the progress back to Amazon.

3.0 Debugging

Unsurprisingly, getting the above functionality working wasn’t as painless as I made it sound.

3.1 Oh you want another book?

Up to this point, I had been testing on the only book that I had in the Kindle web viewer: Wind and Truth by Brandon Sanderson. I figured it was time to expand, so I got a free sample book and ran it through the app, but the content download failed. I compared sample vs. free vs. paid books, but only Wind and Truth was working. Looking at full book metadata didn’t reveal anything.

Codex actually wasn’t much help here, I ended up discovering the issue myself: renderRevision, one of the required arguments for the content download endpoint, was hardcoded to the value for Wind and Truth. I guess it slipped under my AI-slop radar. It’s not the craziest thing; most of the args for the download endpoint are hardcodes (like fontSize, height, width, margins, etc.), and there’s also a kindleSessionId parameter that’s just a randomly generated UUID.

3.2 Corruption

Once I had that fixed, the download worked, but I ran into another error: the .tar download was incomplete and didn’t always have the necessary json files that we needed to reconstruct the text.

Codex did some analysis of the file contents and discovered that all the files were present in the .tar, but some of them were corrupt and didn’t get properly extracted. It thought the issue was on Amazon’s side, but I wasn’t convinced. After some testing, I discovered that copying the raw cURL request made by the browser worked, but making a request from my server with the exact same parameters would fail.

That narrowed it down to the way my server sent requests vs. a raw cURL, and I finally figured it out: the TLS proxy. All requests from my server were being proxied through an external tls-client-api, which is required due to changes in Amazon’s TLS fingerprinting in July 2023 (discovered by the original developer of kindle-api). The proxy mimics Chrome’s TLS fingerprint so Amazon’s servers accept the requests—requests from standard Node.js libraries get rejected because their TLS handshake doesn’t match a real browser.

I hadn’t changed any of the TLS proxy code, and the default setting was to treat every response as text. This worked fine for the original kindle-api functionality of fetching book data, but breaks with tarballs. It basically tries to shove the binary tarball into a UTF-8 string before returning it to our server, which then has to encode it (sometimes unsuccessfully) before writing to disk. Once I added a setting to treat the .tar responses as binary, everything worked perfectly.

4.0 Deployment & Polish

There was still a lot of functionality to add, but the core pipeline was working, so I deployed the app to make sure there wasn’t anything I failed to consider from a deployment perspective.

4.1 Server Deployment

Deploying the server to fly.io ended up being pretty easy. The Dockerfile uses a multi-stage build to install three runtimes—Node (for the server), Python (for text deobfuscation), and Go (for the TLS client)—but otherwise nothing fancy.

As an aside, if you haven’t used fly.io I would highly recommend. It’s not as fully featured as AWS or Azure but is so much easier to work with and makes deployment a breeze for side projects.

4.2 iOS Signing

There were a few options for bundling the iOS app and actually testing it on my phone vs. the iPhone simulator on Mac. Since I’m not planning to publish this to the app store and didn’t want to pay Apple $99/year for a developer account, I went with the free option—sign the app every 7 days when the provisioning profile expires.

There’s a ton of permission/certificate stuff to go through on Mac that I hadn’t done before, but eventually got it up and running! On-demand audiobooks for Kindle that properly sync my reading position.

I was also tired of the empty app icon so I quickly had ChatGPT generate one for me; it looked exactly how you would expect when asking AI to make a “minimal app icon for AI generated audiobooks”:

4.3 Post-Deployment Fixes

The first thing I noticed after deploying is that the app slowed down a lot when using the remote server hosted on fly vs. when I was testing locally. Turns out Tesseract OCR is very fast on my Macbook M4 Pro but not so fast on a tiny 1x shared CPU machine. Easy enough to switch over to using an API from ocr.space, although I had to change from their default engine to “Engine 2” to handle the multi-column text and maintain proper reading order.

Other updates:

Logging: I was getting by with the default logging on the Fastify server / TLS proxy but it was getting a bit painful, so I added proper logging

Security: Someone could theoretically clone my repo, point their app at my server, and use up my TTS credits, so I added a simple server API key (login would have been overkill)

iOS App: I cleaned up the app code to use MVVM architecture and cleaned up the UI a bit

5.0 Additional Features

Time for a few quality-of-life improvements.

5.1 Cartesia + LLM Preprocessing

I was getting close to the credit limit for ElevenLabs and their cheapest subscription didn’t allow for usage-based pricing, so it was time to add another TTS provider. Cartesia had a really impressive demo on their site and is cheaper than ElevenLabs, so I decided to give it a try. They provide time benchmarks at the word level rather than the character level, but that was fine given that my app only sends progress updates every 5 seconds.

To take advantage of Cartesia’s emotion and pause features, I added an LLM layer that puts emotion tags and pauses in the text (along with cleaning up the occasional spacing mistake from OCR). I was really excited about emotion, but it only seemed to work with shorter texts where the entire thing has the same emotion. From the documentation:

Emotion control is highly experimental, particularly when emotion shifts occur mid-generation.

Given that these are long book passages with emotion shifts throughout, it’s not surprising that it didn’t work2. The OCR cleanup + pauses still helped a bit but it takes a while (even with small models like gpt-5-nano), so I left it in as an optional step.

5.2 Partial Generation

I was tired of always generating the full ~8 minutes worth of content, so I added duration selection (1-8 minutes). This had some interesting implications.

First, since the downloaded content covers a fixed range (typically 8 minutes worth), I needed to slice the text to the appropriate length for the requested duration. I used a simple linear proportion—if you request 5 minutes, you get ~5/8 of the text—and aligned the slice to the nearest sentence boundary so audio doesn’t cut off mid-sentence.

Second, there’s the question of overlap: what happens if you generate 5 minutes starting at position 50000, then later request 5 minutes starting at position 52000? For simplicity, I store multiple audio artifacts per provider per chunk, and only reuse an existing artifact if it fully covers the requested range. So if you have audio covering 50000-55000 and request 52000-57000, it will regenerate (the existing artifact doesn’t cover past 55000). This avoids the complexity of stitching audio files together.

5.3 Finishing Touches

A few final additions:

Library: Delete or re-play previously generated audiobooks

Resume: Use current Kindle position to automatically seek to the right spot when resuming playback of a partially-complete audiobook

UI: Proper overhaul to feel more like an iOS app with different tabs; everything was previously on one screen for easier debugging

The final result

So finally, after much strife, I achieved what I sought after: on-demand AI audiobooks that would sync properly with my Kindle.

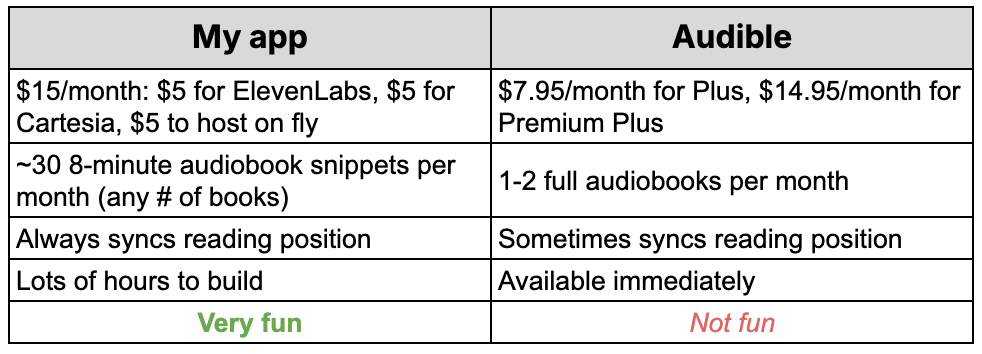

Was it worth it? Let’s break it down:

I think the table speaks for itself.

(See here for the full codebase)

Will emphasize that most of this project was completed in November; coding agents have continued to improve rapidly since then, and parts of it would likely be quite a bit easier if I were to do it today. The journey was still a lot of fun, though.

I could technically stitch together the results from a bunch of different API calls with different emotions, but that seemed like it would be take a lot of integration effort so I didn’t pursue.

Wanna join Kindle?